There is uncertainty in every

decision we make; all we can do is try to make the best decision we can based

on what we know. When it comes to using manure as a fertilizer there are five main

sources of uncertainty, these are:

- Nitrogen need of the crop (due to every growing season being different)

- Nutrient content of the manure

- Availability of the manure nutrients to the crop

- Nitrogen volatilization during application

- Application variability and rate uncertainty

How do we deal with this

uncertainty? What we really want to do is try to minimize each of these

sources, in some cases this may be practical, in others it might be impossible.

For example, manure sampling gives us a good indication of the nutrient content

of the manure, but as we all know manure isn’t always consistent, so it isn’t a

perfect indicator. One way we often hear people handling this is by adding a

little extra nitrogen, some insurance nitrogen, but is that really the best

approach?

I was wondering about this a little

while back, and started to do some calculations to find out how this uncertainty

impacted our manure decision making and this lead me down a trail called the

‘value of information.’ Essentially, it asks if you can now make a better

decision because of something you learned from it, how much extra value does

that add. So I did that for manure sampling (http://themanurescoop.blogspot.com/2014/10/economic-value-of-manure-sampling-and.html) and was pretty happy, but then someone said, even if I

sample I may be more confident about what’s in the manure, but there is still

some error in that so maybe I should still be putting on a little insurance

nitrogen. So I took some time to think on this.

Some background, this is based off

higher nitrogen and corn prices than we currently sit at, something like 2013

corn prices but luckily I scaled then so actual profit isn’t shown and as long

as the nitrogen to corn price ratio didn’t change the results should be

relatively similar.

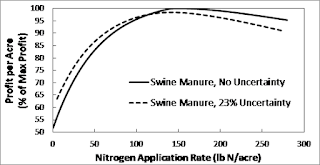

What I did was use the Maximum

Return to Nitrogen calculator (http://cnrc.agron.iastate.edu/) to estimate what my profit would be per acre after field

activities and subtracting the value of the nitrogen applied to the crop above

the MRTN rate (because that was nitrogen you could have used elsewhere). What I

found is that uncertainly in how much nitrogen always lowered our profit as

compared to if we had perfect knowledge. Probably because there was always a

chance of putting on too much nitrogen or too little nitrogen, where if we

really knew the perfect amount we could hit the nail on the head. However, the

interesting thing I saw was that if we did have uncertainty, the ideal nitrogen

rate was just a little lower than when we had perfect knowledge. There were a

few other things I saw though, the chance the manure might have higher nitrogen

content worked to our advantage at low application rates, because there was

potential that in the area where corn yield was really sensitive to nitrogen

application rate that we actually put a bit more on than we were trying to.

However, once we got towards that maximum profit zone we didn’t peak quite as

high, because the uncertainty meant we were never quite hitting that nail on

the head as we always might be a little short or wasting a little.

Figure 1. How does uncertainty change how we should think about nitrogen application? Comparison between perfect and uncertain nitrogen concentration in manure in a corn-soybean rotation (as a note 23% uncertain is what I say using the industry average for your manure is)

Figure 2. How does uncertainty change how we should think about nitrogen application? Comparison between perfect and uncertain nitrogen concentration in manure in a continuous corn rotation.

So what’s the takeaway from all

this? The more we know the more accurate we can be in hitting the nail on the

head and maximizing our profit – but you already knew that (I mean we say

hindsight is 20/20 for a reason), so no surprise there.

The more interesting part was

looking at how putting on that insurance N (just a little extra) impacted our

maximum profit. Essentially what I saw was that a little extra just doesn’t

help us handle that uncertainty. Extra N actually hurts us as we are at a spot on

the yield response curve that is relatively flat and the risk of wasting extra

nitrogen hurts our profit more than the risk supplying that extra N.